Everywhere an Oink Oink: An Embittered, Dyspeptic and Accurate Report of Forty Years in Hollywood

By David Mamet

Simon & Schuster, 256 pp.

When you’ve pummeled the world with as many plays, novels, films, books, cartoons, TV shows, essay collections and radioactive interview remarks as 75-year-old David Mamet, you end up becoming many David Mamets to the public.

And in an age of influencers, each influences the image of the others.

To the theater community, for instance, Mamet remains one of the preeminent American playwrights of the late 20th century, the streetwise master of Mamet Speak—the foul-mouthed, gritty vernacular of success-challenged grifters—and the prize-winning author of modern classics such as Glengarry Glen Ross, American Buffalo and Speed-the-Plow.

Prize-winning, but not beloved. Mamet the culture warrior—the tough-guy Chicagoan who praised Donald Trump “for a great job as president” and announced his shift from left to right in a famous 2008 Village Voice piece, “Why I Am No Longer a ‘Brain-Dead Liberal’”—has turned many in the mainly left theater world against him. From anointment as the bard of the American Dream’s dark side, Mamet now strikes some as a dark-side figure himself. Los Angeles Times theater critic Charles McNulty recently accused Mamet of “right-wing conspiracies and unhinged demagoguery,” calling him a “neocon crank” who’s “hardly been a critics’ darling in his late career.” That’s a sad comedown for a playwright once acclaimed for capturing the unvarnished communication of characters spoiling for a fight.

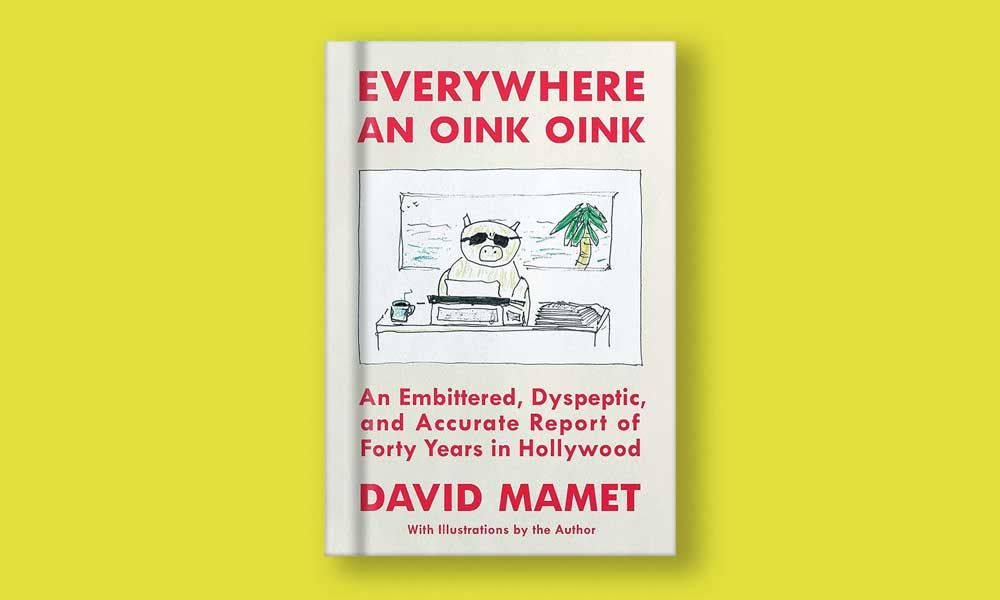

David Mamet. Photo credit: David Shankbone (cc by-sa 3.0)

To another constituency, that of the center-right Jewish community, the author of The Wicked Son: Anti-Semitism, Self-Hatred and the Jews (2006) and other writings on his ethnic heritage comes across as a tribal warrior, defending Jewish tradition and Israel with fierce consistency—if occasional hyperbole. In The Secret Knowledge: On the Dismantling of American Culture (2011), Mamet wrote that “Israelis would like to live in peace within their borders; the Arabs would like to kill them all.” But to Jews on the left, his positioning on many issues within the tribal fold, as well as his attitudes on unrelated domestic issues (opposing COVID-19 protections, disputing climate change), make him problematic, to say the least.

And what of Hollywood, the subject of his newest “embittered, dyspeptic” report, for whom Mamet has been writing and directing films for more than 40 years? (We’ll get to the “accurate” part later on.) The positive take on Mamet is that he was a go-to pro for decades, the fastest typewriter in the West as script-doctor, reviser and writer. The Verdict (1982) and Wag the Dog (1997) earned him Oscar nominations for screenwriting, and critics highly praised some of his directed films, such as House of Games (1987). The downside? The industry word that Mamet can’t take criticism and clashes frequently with producers. As a result, a fair amount of his work has gone unproduced.

Has the ornery playwright who once called critics John Simon and Frank Rich “the syphilis and gonorrhea of the American theater” mellowed?

Through all the multiple Mamets, one personality remains constant: a bold, aggressive, exceedingly confident, superbly well-read, arguably narcissistic provocateur who criticizes American culture in a contemptuous mode so savage it might be dubbed Higher Tourette Syndrome.

Now it’s Hollywood’s turn to take it on the chin. Consider the title Everywhere an Oink Oink. Unlike Old MacDonald, our distinguished author thinks he’s been working in a sty for 40 years, and he’s ready to roast the inhabitants. Has the ornery playwright who once called prominent drama critics John Simon and Frank Rich “the syphilis and gonorrhea of the American theater” mellowed?

A Mamet character might answer, “No f—– way!”

“I am willing to think ill of anyone,” he begins this disjointed assemblage of anecdotes, screeds, scrambled memories and dead-on attacks, “so I suppose I have an open mind.” Everywhere an Oink Oink reads far less coherently than many of Mamet’s earlier nonfiction books and essays. The prose and organization can be a mess. Non sequiturs dominate the book, as if Mamet tossed all his tales and observations on index cards up in the air, then wrote them up as he picked them off the floor.

Mamet’s enemy number one? Producers. They’re “criminal dolts” and “villains” who, “like their kind in Washington, produce nothing.” Actors don’t get off any better. “If the shots are correctly described and engineered into a captivating progression,” Mamet writes, “it makes no difference what the actor says. (Watch a film with sound off, and you’ll see.)”

Whom else does Mamet strafe? “Acting schools load the actor with analyses that clarify nothing,” he explains. “They serve only to kill spontaneity.” Critics? They’re “enraged by productivity,” their “very vehemence” an “indictment of their talentless, loveless, drab, and pointless lives.” (Ouch.)

As he rains invective on the Hollywood zeitgeist, his culture-warrior complaints merge with his professional ones. “The destruction of the Biz by Diversity Commissars is not the cause, but a result, of corporate degeneracy,” he rails, lashing out at “Diversity Porn” and “Diversity Capos.” In his era, “The Theater was a meritocracy.” Now, “The white hegemony in a century of pictures has been replaced by a black hegemony.” (This claim statistically makes no sense, but maybe Mamet isn’t thinking statistically.) “The call for equity is a demand for reward without achievement,” he declares, “and the Studios that heed it are, consequently, turning out garbage.” Really? Black Panther?

Being Mamet—a funny guy who knows everything about the biz—he does score some points. He condemns the endless opening roll call of investor logos that moviegoers now endure and the tiresome producer credits at the end. He shares great lines from others, such as Joe Mankiewicz’s quip that, in Hollywood, an associate producer is anyone who’d “associate with a producer.”

You can also tune out the dyspepsia and focus on the gossip. The man has known everybody. Sean Connery told him, “I never made a penny off of Bond.” Tina Sinatra told him he reminded her of her father. Kubrick told him Kirk Douglas was a “pain in the ass” on Spartacus. The wall of Walt Disney’s inner office, a friend confided, depicted Disney characters involved in an orgy. There’s lots more of that, and it’s fun. Alternatively, you can revel in Mamet’s endless love for puns, some dopey (“Ann-Margret is the only girl in Hollywood who still has her hyphen”), some on the money (“Hollywood is where Nope Springs Eternal”).

Readers who treasure Mamet’s four-square defense of Jews will find passages to like: “Contemporary swine have trotted out the old anti-Semitic canards that the Jews control this or that. If only. Further, the indictment doesn’t specify in what ways Jews exercise this supposed control, and how it injures the ranters who, universally, seem to have done right well in Show Biz whoever controls it…perhaps thanks are more appropriate than invective.”

That said, Mamet exhibits an odd sense of humor about Jewish history. One of the many strange cartoons that festoon the text shows a theater signboard for Shoah. Written below the movie title: “No one will be seated during the last four million Jews.”

The key problem with many of Mamet’s observations—to come to that “Accuracy” in the subtitle—is that they’re just dumb and false. Example: “Inequity, Gender Politics, Feminism, and like doctrines are like modern art: a first glance is sufficient. There’s no information to be gained from an in-depth study.” F. Scott Fitzgerald “wasn’t fit to puke into the same toilet as Hemingway.” Stanislavski’s classic works, An Actor Prepares and Building a Character, “were a bunch of drivel.”

Mamet’s not dumb, so why does he write such things? The kindest way to respond to Everywhere an Oink Oink may be to see it as an elegy from a crotchety major talent embittered by his endgame. Should we forgive Mamet the vitriol because he feels excommunicated from parts of the theater and movie world and this inspires his Lear-like laments?

“I began my career in Hollywood at the top,” Mamet writes, but now he describes himself as “the last cogent survivor of Old Hollywood,” suffering from “senescence,” “sidelined because of my politics (respect for the Constitution, etc.),” the “Hermit of Santa Monica, shunning a world that has moved on, and to which his name is as the mention of Herodotus to illiterate youth.”

Socrates, Kant and many another philosopher thought “knowing thyself” the most important of ethical accomplishments. “Was I arrogant in my fifty years in Show Biz?” Mamet asks. “You bet. But only toward my inferiors. A wiser man might have Gone Further if he had learned not humility but diplomacy. I am not a wiser man.”

Agreed.

Carlin Romano, Moment’s Critic-at-Large, teaches media theory and philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania.

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.