Jewish Film Review | A Requiem for Golda

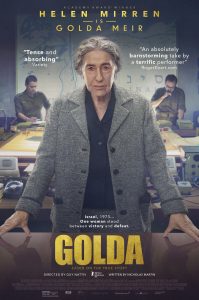

Golda; 2023; 1 hr, 40 min; directed by Guy Nattiv; in theaters August 25

Viewers going into Golda knowing little about the film could be excused for thinking they were about to see a biopic of Golda Meir, who was born in Kiev in 1898, raised in Wisconsin from age 8, moved to Israel with her husband in 1921, and in 1969 became Israel’s first (and to date only) female prime minister. Or, informed beforehand that Golda would instead center on the 19 days of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, they might assume they were going to see a war movie.

But Golda, which opens in U.S. theaters today and stars Helen Mirren in the title role, is neither. Or rather, it’s a little of both and something else.

“The original script was more of a war movie,” says Israeli director Guy Nattiv, whose short film Skin won an Academy Award in 2018. But, he says, he wanted audiences to “get emotional, to feel the character…like Israel’s soul.” Those deeply familiar with the key figures of a half-century ago may find the weight of their preconceptions shifting in various ways watching the film.

Nattiv and screenwriter Nicholas Martin offer a unique character study that follows Meir with a visceral closeness through the war’s tense days, beginning with the surprise attack on October 6, 1973, by Egypt and Syria (aided by other Arab states) in an attempt to reclaim territories taken by Israel in 1967. This assault on the holiest day of the Hebrew calendar, when most Israeli Jews were taken up with holiday rituals, would profoundly impact internal and external perceptions of the war. While Israel initially suffered heavy losses in what came to be known as the Yom Kippur War, the IDF was eventually able to repel the attackers. The United States lent weapons support and later pressured Meir to sign a cease-fire agreement, likely to avoid direct confrontation with the Soviet Union, then the patron of Egypt and Syria. This armistice served as the beginning of the peace process and the eventual recognition of Israel by Egypt. Golda tells this story but is primarily devoted to the prime minister’s experience of it—her dealings with her generals and confidantes, her illness, her anguish.

Mirren truly holds the film together as Meir and was reportedly attached to the film from its inception. Nattiv noted that Mirren was instrumental in his own understanding of the film’s focus, pointing to her performance as another famous leader, Queen Elizabeth II, in a movie with a narrow time frame. (The Queen, for which Mirren won the 2007 Oscar for Best Actress, focuses on the British monarchy’s response in the weeks following the death of Princess Diana in 1997.) Mirren’s portrayal of Meir stuns throughout the film, both in private moments, such as the scenes in which she solemnly receives treatment for the lymphoma that would eventually kill her, and as a leader, when, for instance, Meir settles her squabbling generals with a decisive order.

But where Mirren’s Meir most shines is in her one-on-one interactions. In one such scene, Meir consoles Defense Minister Moshe Dayan (played by Rami Heuberger), who is red-faced and unwilling to enter the war room, having previously humiliated himself in a cowardly outburst after witnessing a horrific Israeli loss to the Syrian army in the Golan Heights. Meir, with a simple “I need you,” coaxes the storied general back into action (although she had, unbeknownst to him, removed him from the chain of command). Meir’s relationship with her personal assistant, Lou Kaddar, and her empathy for a war room stenographer whose son is on the front lines humanize her even as she must make harsh decisions.

Liev Schreiber similarly excels, albeit in a much smaller role, as Henry Kissinger. His portrayal of the former U.S. secretary of state forgoes the usual cliched caricature of Kissinger in favor of a much more subtle performance. According to Nattiv, he and Schreiber had the opportunity to meet the centenarian statesman two days before filming began, allowing the actor to pick up some valuable insights and providing the director with several anecdotes that he incorporated into the film. In one the film’s finest scenes, Kissinger travels to Israel to inform Meir she must agree to a ceasefire or face direct Soviet involvement in the war. Foreseeing Meir’s expert manipulation, the diplomat prefaces their conversation by saying that he is “an American first, secretary of state second and a Jew third,” to which the prime minister replies, “In Israel, we read from right to left.”

Helen Mirren and Liev Schreiber in Bleecker Street/ShivHans Pictures’ GOLDA. Credit: Jasper Wolf, Courtesy of Bleecker Street/Shiv Hans Pictures

In addition to the lead performances, Golda succeeds in creating a palpably tense and insular mood. The most common tool used to that effect is the prime minister’s near-constant cigarette smoking, which creates an anxious atmosphere that overlays Mirren’s calm demeanor. (“I wanted the audience to feel that,” Nattiv said in regard to Meir’s anguish and isolation. “To feel choked.”) Keeping with this interiority, Golda largely eschews any overt or graphic scenes of combat, instead opting to remain inside the Israeli command center, with the military heads reacting somberly to transmissions from troops on the battlefield (in Hebrew, with English subtitles), which, according to Nattiv, were all genuine recordings from 1973.

Where Golda disappoints is in some of the dialogue, particularly with regard to Meir’s top military brass, whose martial pomposity often verges on the absurd. Some of the weightier lines come off as almost silly. The most notable of these is when Moshe Dayan declares, without much in the way of emotion, “We will crush their bones; we will tear them limb from limb.” Moreover, the brisk pacing of the film is punctuated by some awkward scenes that attempt to capture Meir’s inner turmoil, most evidently in the form of an extended nightmare sequence that occurs roughly two-thirds of the way in. Here, a harried Meir is seen shouting and slamming down an infinite number of ringing telephones. The scene comes off as overwrought given Nattiv’s superb use elsewhere of closeups and textures—the deep lines on Golda’s face, her unkempt hair and the clouds of cigarette smoke she expels that linger in the confined space of her modest bedroom and the other secure locations that confine her.

Some of the source material for the film comes from first-hand accounts of several people who were close to Golda Meir during the tense weeks of war, including her bodyguard Adam Snir. And much comes from the Agranat Commission of 1974, which investigated what was seen as the failure of Israeli intelligence to intercept plans of the Arab attack and Meir’s handling of the military response. A trove of documents produced by the commission were declassified a decade ago, and since then a fuller story has emerged.

Helen Mirren, Rami Heuberger, Lior Ashkenazi and Dvir Benedek in Bleecker Street/ShivHans Pictures’ GOLDA. Credit: Sean Gleason, Courtesy of Bleecker Street/Shiv Hans Pictures

One of the revelations conveyed in Golda is foreshadowed early in the film. Meir and her military advisers are considering the possibility of attacks by Arab forces, but they don’t have anything firm to go on. “Of course war is coming, but when?” she asks. Later on, in what might have been a major plot point, Meir learns that one of the main reasons the Israelis were caught off guard by the attack was because its surveillance apparatus, which in the film they all simply call the “listening device,” had accidentally been turned off. This explanation is treated with something of a shrug, both by the film’s characters and its director. “It was a f—k up,” Nattiv said when asked why it wasn’t a larger part of the story. Golda doesn’t explore if there was any intention behind the mistake. Instead, staying true to its focus, the film centers Meir in front of the camera and eventually in front of the commission, lighting one cigarette with another and essentially taking responsibility. She delivers a moving response to questions about the number of Israeli casualties, removing a ledger from her handbag in which we’ve watched her dutifully record the numbers of fallen soldiers reported to her. While Meir was cleared of direct responsibility for the war by the Agranat Commission, she resigned that same year.

Born in 1973 just five months before the Yom Kippur War, Nattiv recalls that when he was growing up everyone knew who Golda Meir was—schools were named after her and her face was on the 50-shekel bill—but her legacy was primarily associated with Israel’s ill-preparedness and the terrible losses from that war. “All political careers end in failure,” she says at one point to a young Ariel Sharon (Ohad Knoller). Nattiv came to see her as the war’s scapegoat and endeavored to tell the story from a different perspective, stating: “If I could have called the film ‘Requiem for Golda’ I would have.”

Access Moment’s Moment’s Film and Movie Reviews.

Note: In May, as part of the upcoming 50-year anniversary of the Yom Kippur War, the IDF Archives at the Ministry of Defense launched an interactive website (in both Hebrew and English) containing over 20,000 files. It features documents, photographs, maps, and sound clips related to the war, some newly declassified.

Top image: Actress Helen Mirren portraying Golda Meir in the film “Golda”. (Photo credit: courtesy of Bleecker Street/Shiv Hans Pictures)

One thought on “Jewish Film Review | A Requiem for Golda”

My husband and I saw the film and thought it was well done. It certainly brought back memories of that time which was not long after our marriage.