Much ink has been spilled on director Taika Waititi’s portrayal of Hitler in his Nazi satire Jojo Rabbit, which just won the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. Some have praised Waititi’s take on the genocidal ruler, saying that his light and humorous version of the dictator provides useful social commentary on how we approach political tyrants. Others were not impressed, arguing that the director’s message failed to dig into the horrors of the Nazi regime and its leader.

Less attention, however, has been paid to Sam Rockwell’s Captain Klenzendorf, a murderous Hitler Youth camp director with a strong hatred of Jews. Throughout the film, Klenzendorf takes a liking to Jojo, serving as a surrogate father figure to the young boy’s imaginary Hitler. When he discovers that Jojo is hiding Elsa, a young Jewish woman, in his home, he helps protect both of them from Nazi investigators. His turn away from the dark side reaches its climax when he sacrifices himself to save Jojo from Soviet troops. By the end of the film, he is a hero. He is, for lack of a better term, a nice Nazi.

No doubt there were Nazi officers who showed kindness to their countrymen while the regime held power, all while upholding and partaking in the horrifying status quo. Exploring the “nice Nazi” in film and observing the paradox unfold on screen would make for a fascinating study into both the characters in question and the audience watching.

In an age of growing anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial, however, one wonders if Waititi is behind the times here. The hate-filled comments Jews see every day on social media manifested themselves during the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, where marchers chanted “Jews will not replace us” and waved Nazi flags during the procession. The number of Jewish institutions—from synagogues to cemeteries—that have been vandalized with Nazi imagery continues to grow. The attacks in Pittsburgh, Jersey City and Monsey sent shivers through the American Jewish community, with some questioning their place in contemporary society.

It is against this backdrop that Waititi presented the character of the “nice Nazi.” While I don’t doubt Waititi’s intentions, the character of Captain Klenzendorf ultimately does more harm than good. Thanks to both Waititi’s writing and Rockwell’s excellent performance, they create a sympathetic character that one can’t help but love. His arc is rich and fulfilling and, by the film’s end, Klenzendorf is less hateful indoctrinator and more misunderstood fun uncle. Heck, he was my favorite character throughout the film’s run.

At the same time, movies are more than just pictures on a screen. They create powerful imagery and narratives, sometimes ones that stick with viewers for years. Characters, especially those based in history, take on more than their immediate storylines. They live beyond the screen. When one creates a movie about Nazis, they are not just commenting on Nazism. They are showing you what it means to be a Nazi.

With a character like Klenzendorf, Waititi makes viewers sympathize with a group that deserves no sympathy, creating a false narrative that one could easily see gain traction on the far left or right, despite the filmmaker’s intentions. At best, it turns Nazis into a joke. At worst, it transforms them into misunderstood heroes. The results, however, are the same. By presenting the “nice Nazi” in fiction, Waititi has opened the door to the creation of the nice Nazi in reality.

Jojo Rabbit may not be the spark that will ignite a nuanced discussion of the Nazi party and its officers. But nothing exists in a vacuum. As truth becomes harder to discern and social media amplifies voices of hate, how long before we start listening to pundits and historians argue that not all Nazis should be defined just by their party affiliation? How long before we start hearing that genocide is complicated and that these murderers also did good in the world, raising families and giving charity? How long before we start hearing that these kind-hearted souls were just following orders? How long before we start hearing that there were very fine people on both sides?

Captain Klenzendorf would be less of an issue were Waititi’s satire of the Nazis stronger. However, he fails to effectively skewer them, presenting them as a group of bumbling idiots instead of the systematic and ideological organization they truly were. The film has nothing to say about Nazism’s core, making one wonder why Waititi chose to focus on it in the first place.

That is not to say that Nazi satire is not possible. Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator showed that it was okay to laugh at the Third Reich and its leader. Mel Brooks’ The Producers followed suit with its in-movie play, Springtime for Hitler. And, while not satire, The Boy in the Striped Pajamas told a heartbreaking story that allowed us to sympathize with a Nazi commander, while also not forgetting who he was at his core.

However, what separates those movies from Jojo Rabbit is that they were created in a world where Nazim was believed to have been utterly defeated—or at least pushed to the fringes. Today, however, the opposite is true. In our world, Springtime for Hitler could be viewed not as satire, but as propaganda.

Sam Gelman is a news editor at CBR, where he covers comics, movies and TV. He is also the communications and program officer at the Yeshiva University Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. You can follow him on Twitter @SamMgelman.

But there WERE good Germans, and there ARE bad Americans. If Springtimefor Hitler worked 50 years ago as satire, it works today. It’s not Watititi’s job to make us realize that Hitler was a monster (but he does that effectively with the 5 Gestapo agents who come to the house). Hes not presenting a sympathetic picture of Nazis. The movie going public is smart enough to realize that this isn’t a recruiting film.

After seeing this film twice, I believe that Klenzendorf was actually a member of the resistance–for all the things mentioned in the article and more, including his emphasis with Jojo, after Rosie’s death, that she was not just a good woman, but a really good woman. But even if untrue, he did many good things and definitely qualifies as a good German doing his best. As for being a Nazi, there were no signs that he bought into it, and refusal to sign up would have been life threatening.

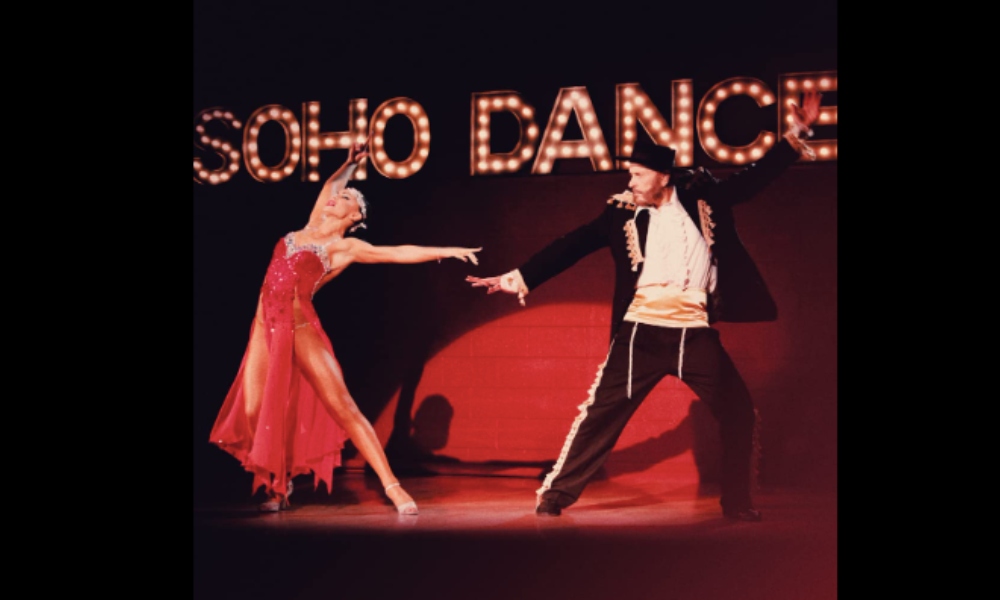

I am glad the editors used this picture to illustrate the article because it also illustrates how much the author missed the subtext of these two characters. In this climactic scene they are both wearing pink triangles. They were homosexuals and members of a minority oppressed by the Nazis. They have normal German army uniforms, rather than Waffen-S.S., that they then “make fabulous.” There is no proof that they bought into the National Socialist ideology (unless the author wishes to paint all Germans as Nazis and disregard conscientious objectors and dissidents who were murdered in the concentration camps).

The author might also be surprised to learn that Waititi is Jewish.

Luckily for us, Nazi leaning Americans would never watch this movie! I loved Rockwell here, and at no point did I ever think that Nazism is acceptable. If one gets this from this movie, he/she have already crossed that line.

Spot on!

Oh wow, you really missed the character’s point entirely, Captain K’s nature isn’t about a “nice Nazi”, it is about a man trying to hide his sexual preferences in a time and place when he could have been murdered by it!

I think it’s important to show that bad people can become good and be redeemed. Otherwise why would a bad person even bother trying to change?

Wtf, Klenzendorf was never a jew-hater. From the very beginning he was annoyed with the rhetoric and wastefulness of the regime. If you pay attention to him, he never shows any enthusiasm about his job. In the book burning scene, he is looking wistfully on while drinking, as everyone else celebrates. Klenzendorf isn’t really a “Nazi” at all, he’s just a person, which is what the film is all about. It uses Elsa and Jojo as a bit of an analogy for how we view Nazis and extremists in general. They are all people, and are “bad” for different but understandable reasons. Jojo goes through the film thinking Jews are evil people with scales and mind control powers to understanding they are normal people just like us. The ending of the film alludes to this too. The same silly propaganda that is spouted about the Jews in the first act is regurgitated by Yorki at the end about the Russians, who are often also slandered in the same way. Jojo is another example, his mother loves him but recognizes he is a fanatic. Regardless of this, she knows her son is somewhere there.

Thats what Captain K is. He is another example of how these “extremists” are just people. However while we see some extremists in transition, some who never seem to really grow out of it, Klenzendorf is one who has already grown out of it long ago, and understands what makes it so bad.