With

Gal Beckerman / Nicholas Delbanco / Nathan Englander / Rebecca Goldstein / Allegra Goodman / Mohsin Hamid / Dara Horn / Aaron Lansky / Ruby Namdar / Alicia Ostriker / Robert Pinsky / Jane Yolen

As Moment’s culture editor, whether I am speaking with publishers, authors, scholars or people I meet during Shabbat morning kiddush, sooner or later I am inevitably asked the same question: Are great American Jewish books still being written? Despite the popularity of the question, it is out of date. In just the last decade, there has been a revolution in what constitutes a Jewish text. Many of the best and most powerful Jewish “books” now come in the form of films, TV shows, podcasts, graphic novels and, some might even argue, tweets. Absent the constraints of the bound written page, these Jewish “books” allow previously unheard voices to emerge. For instance, virtually no mainstream novels have been written from the African American Jewish perspective, but the 2014 documentary film Little White Lie focuses a compelling lens on the experiences of a biracial Jew. Similarly, podcasts such as “Really Interesting Jews” introduce us to new voices discussing topics as wide ranging as the Hogwarts Haggadah and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. From zombies to incest to martial arts and meditation, for today’s American Jewish authors, everything is on the table and open for discussion.

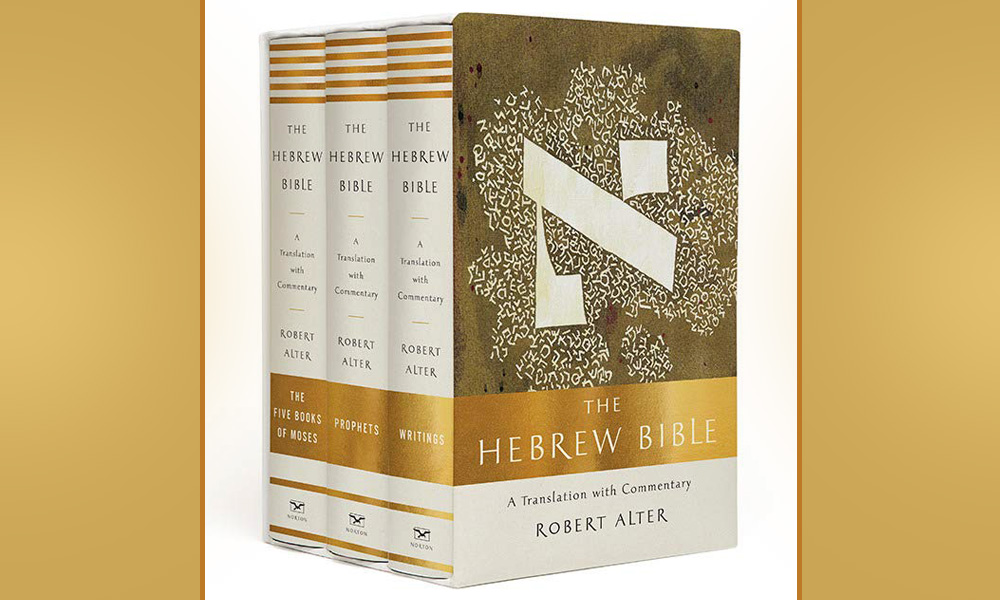

Traditional books persist as a popular and important genre. Jews remain the people of the book; we still read and love them. But even here, there have been significant changes: New, often small, Jewish publishing houses are printing books that formerly would have been overlooked by mainstream publishers—Jews Versus Aliens from Ben Yehuda Press was one of 2017’s most delightful surprises. Self-published books have become a rich source of Jewish writing with creative approaches to traditional topics and tropes: Most importantly, self-publishing represents the true democratization of Jewish literature.

As much as I believe that this is a time of great vitality and exciting transformation in American Jewish literature, I am concerned by who and what we are not reading. Powerful gatekeepers narrow the scope of what we read. Now, more than ever before, book publishing is big business. As a result, fewer books and still fewer authors garner a disproportionate share of critical attention and financial gain. Relatively few people are aware of, let alone reading, myriad other offerings. Sadly it’s entirely possible that the best American Jewish books of 2018 may go unnoticed and unread.

However uncertain the future of the traditional book itself—it’s not clear that the book as we know it will exist in 50 years—the American Jewish literary voice remains vital, uniquely (and distinctively) both particular and universalistic and, most of all, ever changing. In the following symposium, Moment asks some of the noted writers of our time to weigh in on the evolution and well-being of American Jewish literature.

Dara Horn

Dara Horn

Dara Horn is the author of five novels and a two-time winner of the National Jewish Book Award in 2003 and 2006. Her most recent novel is Eternal Life.

There are so many ways in which American Jewish literature has evolved in recent years; the most obvious one is that “being a Jewish writer” has gone from a career-killer to a marketing hook. Decades ago, it was de rigueur for writers to avoid this label; today, hundreds of writers compete for coveted slots in the country’s many robust Jewish book fairs.

But even that is old news by now. What I find intriguing about current American Jewish literature is a new and varied engagement with Israel—not only American writers who take their characters to Tel Aviv, but Israeli writers who are changing the American Jewish landscape. Two completely unrelated novels come to mind: Shani Boianjiu’s The People of Forever Are Not Afraid (2012) and Ruby Namdar’s The Ruined House (2017). The first is a novel about female Israeli army veterans, set entirely in Israel—but written in English by its native Israeli author. The second is a novel about a secular American Jewish professor in New York whose strange visions of the ancient Temple slowly consume his life—written in Hebrew by an Israeli who resides permanently in New York and only newly translated into English.

Beyond fiction, we also now have phenomenal memoirs bridging the diaspora-Israeli experience from so many angles, from Matti Friedman’s Pumpkinflowers (2016), about a Canadian immigrant’s experience defending Israel’s northern border in the 1990s, to Ilana Kurshan’s If All the Seas Were Ink (2017), about an American in Jerusalem whose personal struggles lead her to undertake daf yomi, a seven-year study of the entire Talmud page by page. We hear a lot these days about how Israel and the American Jewish community are drifting apart, but literature tells a different story—a new and thrilling story that will reshape the future.

Nathan Englander

Nathan Englander is an author whose short story collection What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank was a finalist for the 2013 Pulitzer Prize. His most recent novel is Dinner at the Center of the Earth.

I am here because of the writers that came before me. There was a huge moment in American literature in which Jewish American writers were suddenly on everyone’s nightstand. Saul Bellow, Philip Roth and Grace Paley changed the landscape for how people read. Their stories were universal. They broke ground in America.

Now you hear more voices and different kinds of voices. We have voices from every front, whether that’s sexual orientation or religious identity. There was a time when Jewish writers were really swimming upstream. Now we are able to be out there in a different way from those who came before us. The definition of what’s “other” or “outside” has changed. Jews as a subject matter should not now be seen as an “other” or as a “type” of writer.

Despite lots of Jews and Jewish content in my novels, I feel like Jewish literature is just part of American literature. I am uncomfortable with the idea that there currently is a genre of American Jewish literature. I don’t write about Jews; I write about people. That said, I think it’s a great time for literature, and there are a great bunch of Jewish writers doing amazing work.

There are themes that are outside of time and that run across the generations in Jewish literature—anti-Semitism or Israel, for instance. I can step back and look at Jewish literature as a category over time, but I do not usually frame things that way. My recent book is about my personal heartbreak about seeing the peace process come apart. You can make that into an “Israel” book or one about right and wrong or about empathy. At its core, I am concerned with justice and injustice.

I read a ton of American Jewish literature. I was shaped by it. The fact that my world ends up being a Jewish world or that my metaphors are Jewish metaphors or that my logic is Talmudic is because that is a complete and whole universe to me.

Allegra Goodman

Allegra Goodman

Allegra Goodman is the author of eight books, including Kaaterskill Falls, a finalist for the 1998 National Book Award. Her most recent novel is The Chalk Artist.

This is a time with many great American Jewish writers. A generation or two ago we would have spoken mainly of Philip Roth, Saul Bellow and Cynthia Ozick. The people who were writing American Jewish literature in those days were, for the most part, secular Jews who were ambivalent about religion. Philip Roth is very Jewish, but he is extremely critical and even harsh in his characterizations of Jews and Judaism. He is also very sensitive; he was hurt and angered when people said he was anti-Semitic. These early writers were culturally Jewish and very political. Subsequently, American Jewish writers have become much more comfortable writing about religious practice and ritual. Ted Solotaroff wrote a major essay in The New York Times Book Review in 1988 in which he discusses a generational shift in American Jewish literature as novelists began to explore the religious dimension of Judaism as well as its cultural dimension. Cynthia Ozick and Chaim Potok were pioneers in this, but younger writers have really taken up these topics. They have embraced writing about Judaism in a more spiritual way, not just culturally. That’s been a big shift.

Today’s authors like to write about their search for Jewish identity. They have grown up one way and are searching for another way to be Jewish. Tova Mirvis comes to mind. She is part of a sub-genre of memoir writers: Jewish women writing about growing up Orthodox or in very cloistered communities and then breaking with those traditions. American Jewish writers such as Jonathan Safran Foer, Nicole Krauss and Michael Chabon are all more interested in Jewish tradition than were older writers. They comment in increasingly complex ways on Israel and the Holocaust, on the nature of diaspora, on the Jewish past and on the appeal of ritual and the force of assimilation. Through their characters, plots and books they are more willing to talk about their personal spiritual connection to Judaism and Jewish history.

What we have in common today as American Jewish writers is that we like to go our own way, that our Jewish backgrounds are diverse, that our picture of American Judaism is often fractured, unbound by time and place, and that we don’t feel a particular allegiance to New York City or to our parents’ Judaism. Indeed, our parents’ Judaism was not their parents’ Judaism. The constant here is change.

Ruby Namdar

Ruby Namdar

Ruby Namdar is an Israeli novelist of Iranian-Jewish descent. His latest novel, The Ruined House, won the 2014 Sapir Prize, Israel’s most prestigious literary award.

As an Israeli writer living in New York, I’ve noticed that American Jewish authors often don’t want to be identified as American Jewish authors. Despite that, they do an amazing job exploring Jewishness. Jewishness is the everyday experience of actually being Jewish rather than a theoretical idea of Judaism. From Chaim Potok’s 1967 The Chosen to Henry Roth to Philip Roth through to today, American Jewish literature has always been distinguished by authors trying to figure out what it means to be Jewish. The new twist is that the current generation also wants to know what it means to be a Jewish writer or a Jewish artist. For instance, Nicole Krauss’s ambitious and grand Forest Dark explores what Jewish literature and authorship are. The main art form shared by the various Jewish tribes around the world has always been verbal and written art. So it makes sense that when American Jewish authors today try to understand Jewishness, they examine literature.

American Jewish literature and Israeli literature are currently developing in polar-opposite directions. The Jewish element in current Israeli literature tends to be very marginal. In Israel, authors are concerned with the meaning of living in Israel—their work is about Israeliness, not Jewishness. David Grossman’s Man Booker International Prize-winning novel, A Horse Walks into a Bar (2017), is not a Jewish novel in the overt or traditional sense of that term; there are no openly Jewish themes in the book. And David Grossman is the leading voice in Israeli literature today. Very few Israeli authors today write about Jewish religion or culture. Historically, Israeli literature focused on ideology and the meaning of the collective; now it is more about the stories of individuals. In America, literary themes are becoming more universal; in Israel, they are getting smaller, and you are more likely to read about the crisis of the individual. Israeli authors don’t want to deal with collective questions any more; I think that’s the result of living in an ideological pressure cooker. Fatigue has set in. Younger Israeli authors don’t want to take on big existential questions.

Alicia Ostriker

Alicia Ostriker

Alicia Ostriker is a poet and a scholar. She has twice been a finalist for the National Book Award. She currently serves as a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets.

For me, the two great events in current American Jewish poetry are the explosion of women’s poetry (including poetry by openly gay women), and of midrashic poetry (including poems that openly question Jewish traditions). But first some words about the past: W. H. Auden asserted that “Poetry makes nothing happen.” On the Statue of Liberty is a poem by American Jewish poet Emma Lazarus that refutes his assertion. The words “Give me your tired, your poor / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…’ made something happen. They changed the meaning of the statue, the meaning of the Port of New York City, and the meaning of America. Our stance of welcome and opportunity has been our greatness. But through most of our history, every fresh wave of immigrants has been despised —and we are on the brink of regressing to a similar grim narrowness.

The optimism of Emma Lazarus is no longer with us, either in American poetry or in Jewish poetry. Yet the opening of Jewish poetry to specifically women’s experience is surely a positive development. Some examples: Maxine Kumin’s affectionate and rueful poems of family life with, as one critic said, “an excess of maternal genes,” coincide with her poems of farm life and the environment. My own poems of marriage, childbirth and motherhood dovetail with the Jewish injunction to “choose life,” and could never have been written before the feminism of our era. Marilyn Hacker’s lesbian poetry relates to her passionate political poetry. For Irena Klepfisz, “words in the mother tongue” are not merely metaphoric; Klepfisz’ advocacy of Yiddish, her memories of the Holocaust, her social advocacy, her lesbianism, and her critique of the Israeli occupation are all intrinsically entwined with the death of her father in the Warsaw uprising and with her ongoing closeness to her mother. To look at contemporary Jewish women’s poetry is to see work that involves family life, and the sensuousness of everyday experience—it puts these things together with the demands of “justice, justice shall you seek,” in a way that no poetry ever did before.

Midrashic poetry is everywhere today. By my own highly unofficial count, something like 80 percent of today’s midrashic poetry is composed by Jewish women. Naturally, as they (we) enter the tents/texts previously occupied by male rabbis, scholars and interpreters, they (we) have a lot to say. Biblical female characters such as Lilith, previously silenced or demonized, suddenly find their voices. So does poetry foreshadow a change in politics? Emma Lazarus’s poem did so. Might it happen again? There is no telling.

Gal Beckerman

Gal Beckerman

Gal Beckerman is an editor at The New York Times Book Review. His book When They Come for Us, We’ll Be Gone won both the 2010 National Jewish Book Award and the 2012 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature.

There is currently a cadre of American Jewish writers—Michael Chabon, Nicole Krauss, Jonathan Safran Foer—who are willing to be identified as Jewish writers and who will sometimes touch on Jewish themes or have Jewish characters at the center of their books. Their books stand out because although they are targeted at mainstream audiences, they are not parochially Jewish. They are still interested in exploring questions of Jewish identity.

Good fiction comes from points of tension and conflict. So I have some concerns about the limitations of this kind of American fiction and where American Jewish fiction will come from in the future. For American Jewish authors in the past, great books have fed off the tensions between tradition and modernity; they have grappled with making ancient religious values relevant and with anti-Semitism and confronting one’s own sense of being an “other.” These are all big, traumatic and juicy themes. I’m not sure they exist right now in the lives of most Jewish American writers.

There is, however, more openness now in Jewish American writing and a willingness to fully explore Jewish tradition. Women such as Tova Mirvis and Deborah Feldman, who have left the closed world of the Orthodox, are writing freely about their experiences. They are a new kind of American Jewish writer investigating a rich area of tension. Also, and again more from women writers, is a new engagement with text and Torah. Dara Horn, for instance, is deeply invested in writing fiction that is in conversation with Jewish sacred texts. That follows somewhat from Cynthia Ozick, but it’s a huge departure from Philip Roth.

Many of us have been struck by the number of American Jewish authors who have recently written novels about Israel. I think this is because Israel generates tension for them. Pessimistically, you could say that this shows that American Jewish writers no longer have anything to say about what it is to be a Jew in America. They are either totally assimilated or they have been embraced by America to a degree that they no longer have any conflicts. Positively, you could assert that Israel is a rich source of conflict and authors see it as an interesting place. As an Israeli American, I am heartened to see Israelis emerge in American Jewish fiction in a full and multi-dimensional way. In contrast, the Israeli who suddenly appears at the end of Philip Roth’s 1969 Portnoy’s Complaint is a kibbutz girl and could not be more of a stereotype. Today, for American Jewish writers, Israel is a real place, not an abstraction. I think that’s progress.

Jane Yolen

Jane Yolen

Jane Yolen is an author of more than 365 fantasy, science fiction and children’s books, including the 1989 National Jewish Book Award winning The Devil’s Arithmetic.

For a long time, the only kinds of Jewish children’s books that mainstream publishers were interested in were books about holidays or the Holocaust. They were not interested in books about everyday Jewish life. The All-of-a-Kind Family books by Sydney Taylor published in the 1950s were almost one of a kind for a long time. Then, very slowly, you started to get books that showed Jewish kids in ordinary settings—even if they were fantastical settings—rather than showing them celebrating Hanukkah or Simchat Torah. For the most part, these books did not sell well, so most Jewish children’s books are still about holidays or the Holocaust. You don’t have many books about Jewish kids getting bullied because of their religion or struggling with their religious identity.

I am a 78-year-old Jewish writer; I don’t believe that the Jewish story books I wrote decades ago would get published now. We no longer publish what we love; we publish what we can sell. The problem is that non-Jews don’t tend to read Jewish children’s books. Jews read widely. They read story books about both Jews and non-Jews. The reverse is not true. These days there needs to be a marketing hook to get a story book published. It’s no longer just a matter of an editor liking your book. Jewish authors have tried to broaden the themes in Jewish children’s books, but usually publishers are simply not interested. The inability to get books published has changed the character of what authors write for Jewish children.

The market for Jewish children’s books is much smaller than if you want to write for the larger market. In some ways, as Jewish authors, we’ve actually caused this by writing so many Holocaust novels and holiday stories. We have made Judaism something odd, something magical or mystical. This also happened when authors were writing stories about the magical mystical Orient: “They” were not like “us.” So as writers, we are partly at fault for this happening in Jewish children’s fiction. Furthermore, there are now various small companies publishing fiction for Jewish children. This may well result in Jewish children’s fiction being in a kind of ghetto and becoming excluded from the larger body of children’s writings. It’s too soon to know.

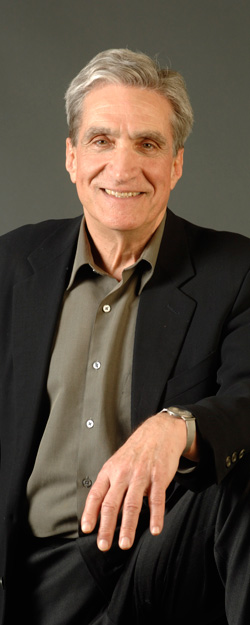

Robert Pinsky

Robert Pinsky

Robert Pinsky served as Poet Laureate of the United States from 1997 to 2000. Pinsky, the author of 19 books, is a professor of creative writing at Boston University.

Writing by Jews in the United States today has an interesting, ever-changing relationship to the majority religion. Christianity not only saturates the language, the architecture, the visual art, it also unites—at least nominally—Americans of different opinions, ethnicities, kinds and origins.

Outside that umbrella, or near its borders, like an American writer raised in the identifying context of Islam or of an Asian religion, the contemporary Jew offers an experience on the intimate level of speech or on the civic level of politics, and every gradation in between, that is simultaneously inside and outside, native and imported.

Beyond that, there is nothing anyone can predict, much less prescribe.

In 1994, my translation of The Inferno of Dante appeared, enhanced by Michael Mazur’s great illustrations. The monotype of Mike’s originals went to museums around the country, and he and I did a speaking tour. More than once, we were asked for our thoughts about two Jews collaborating on a work that has been called the great Christian epic. Mike and I both felt that our work extended a lifelong, perpetual, daily process of accommodating, or arrogating, aspects of the majority culture. Inferno was just one more example. Mike’s examples of that familiar process were from painting. I mentioned Shakespeare. And I cited the example of Irving Berlin, who wrote “White Christmas” and “Easter Parade” as part of the ongoing, cosmopolitan, syncretic nature of American song, art and literature. Inside and outside, native and imported, reflective, but not as static or rigid as a mirror; in a better metaphor, more like our national food that is Italian and Chinese and Mexican, only not. Even wieners and frankfurters have their particular, deep historical identity, as words and as places of origin and as sausages—kosher or not.

Nicholas Delbanco

Nicholas Delbanco

Nicholas Delbanco is the Robert Frost Distinguished University Professor Emeritus of English at the University of Michigan. He is the author of 29 books of fiction and non-fiction. His most recent novel is The Years.

My first sustained exposure to a major American Jewish author was to Bernard Malamud, who was my senior colleague at Bennington College in Vermont. Malamud is clearly among the constellation of important American Jewish writers of prose, but he resisted that label. He thought of himself as an American author who was also Jewish. That distinction stays with me. I don’t like to think of Jewish writing as a subcategory of American literature any more than I like to label people Southern American authors or Black American authors. That said, what Jewish American writers have in common with each other is a particular kind of cultural alertness and ancestral history. It’s not an accident that we are known as the “People of the Book.”

The great trio of 30 or 40 years ago was Malamud, Bellow and Singer—the latter two both Nobel laureates. They were succeeded, if not supplanted, by such authors as Cynthia Ozick and Philip Roth. We are told that Roth has laid down his pen, but Ozick remains a singular presence in American letters. Unflinching in her intellectual rigor, unapologetic in her embrace of Judaism and willing to fuse the mythic and mundane, her voice is hers and hers alone. Yet a common denominator of these authors is a sense of enforced assimilation and the novelty of being strangers in a strange new world.

For more recent Jewish writers, the fact of being American is more or less taken for granted. There are exceptions, of course; think of André Aciman’s Call Me By Your Name, where there is still a sense of transplantation and a new identity. Or Michael Chabon’s Moonglow, where the grandfather’s experience impacts and inflects that of his grandson and scribe. But most current Jewish authors have not been washed ashore; they are part of the national mix. The act of parental (or grandparent’s) assimilation itself creates a shared identity. Their writing is a variation on a theme of being American rather than astonishment at discovering that that’s who we are.

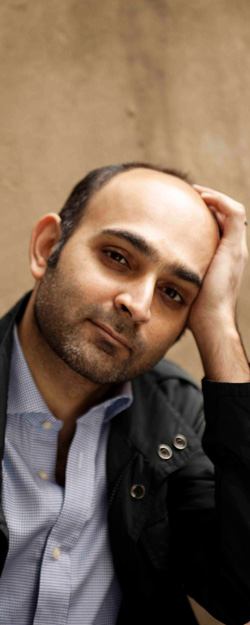

Mohsin Hamid

Mohsin Hamid

Mohsin Hamid is a Pakistani novelist and writer. His novel The Reluctant Fundamentalist was shortlisted for the 2007 Man Booker Prize for Fiction; his most recent novel is Exit West.

As a Pakistani writer, I have been greatly influenced by many American Jewish authors —Philip Roth and Saul Bellow, as well as European Jewish writers such as Primo Levi and Martin Buber, especially come to mind. However, I don’t think of Jewish literature as a distinctive category in current American literature. I consider contemporary American Jewish writers to be American writers.

The older generation of Jewish writers helped establish what American literature itself is, especially for those of us outside the United States. For instance, the powerful and often tragic novels and short stories of Henry Roth about the Jewish immigrant experience in Depression-era New York bring the American tenement slum world vividly to life. Saul Bellow and Woody Allen, both giants in American Jewish literature, created a witty and wonderfully distinctive voice and language for American writing overall. These clearly Jewish writers continue to play a key role in the identity of American literature all over the world.

As someone who has often lived abroad as part of the Pakistani diaspora, the exploration of diaspora in American Jewish literature has had an enormous impact on me. The classic American Jewish authors gave a powerful voice to the outsider experience. They have helped me explore what it is to be a minority. Also, the humor found in the American Jewish literary tradition influences current Pakistani, South Asian and Middle Eastern writing. It shows a way to make loss tolerable and to potentially destabilize and poke fun at the powerful.

I’m drawn to contemporary writers such as Nicole Krauss, Jonathan Safran Foer and Nathan Englander, who deeply explore the personal meaning of their Judaism in specific contexts. Perhaps born of desperation and frustration, particularly in terms of a more complex and conflicted relationship with the State of Israel, there are new forms of politically impassioned work from these and other American Jewish authors. Disagreements and discomfort with the current Israeli government are a new thing for many of them. They are not used to having strong negative reactions to actions being taken by Jews in the name of other Jews. They are exploring how to balance speaking out against injustices while, most often, also supporting the State of Israel. I suspect that the Trump era will further catalyze this politically engaged fiction. Many of these contemporary writers are also interested in recapturing a meaningful spirituality. They are struggling to find a new and authentic spiritual voice in an environment where spirituality has become deeply politicized.

Aaron Lansky

Aaron Lansky

Aaron Lansky is the founder and president of the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts. He is the author of Outwitting History: The Amazing Adventures of a Man Who Rescued a Million Yiddish Books.

I think there is potential for great American Jewish literature today, but I don’t think it has been fully realized. The challenge of contemporary Jewish literature generally is to find sufficient Jewish density to sustain ongoing literary creativity. From the mid-19th century, modern American Jewish literature has concerned itself with how to redefine Jewish life in the modern world. Earlier American Jewish writers, especially those writing in Yiddish and Hebrew, had incredibly dense Jewish lives to base this inquiry on. They had studied in cheders and yeshivot; they had deep knowledge of traditional Jewish sources and of the textures of daily Jewish life. They were able to embrace modern Western literary expression and use it to explore this wellspring of Jewish experiences. For the next generation, with authors such as Philip Roth and Saul Bellow, their Jewish knowledge didn’t run as deep, but they knew the sociology of the American Jewish experience. In 1959, when Grace Paley wrote “The Loudest Voice” about a Christmas pageant put on by Jewish students in a school in the Bronx, she had an extraordinary sense of juxtaposition between the Jewish and American worlds. She lived in a neighborhood with a Jewish ethos. You just don’t find that now. The great Yiddish American writer Shalom Aleichem similarly captured the nexus between Hebrew and Yiddish high and low culture in daily Jewish American life. He wrote books that were quintessentially Jewish and caught the dialectical tension between Jews and the outside world.

I am not pessimistic about the current state of American Jewish literature. However, we need to be more proactive. We can’t create new modern American Jewish literature out of nothingness. Absent the density of daily Jewish experience and background, future writers will need greater knowledge of Judaism, Jewish literature and culture. In Jewish day schools in the United States, they don’t usually teach modern Jewish literature. Ironically, you are more likely to meet those books in public schools. We need to promote this aspect of Jewish education in creative ways. It’s a good sign that there are a large number of readers who are passionately interested in Jewish literature and culture, including in Yiddish. Younger Jews are growing up in a world that celebrates diversity. They want to understand their place as Jews in this broader cultural mosaic. They know that they are heirs to an extraordinary literary tradition, and they are eager to understand what that’s about. If we can capitalize on that intellectual curiosity, we can potentially have a greater renaissance in American Jewish literature than we have ever seen before. After all, American Jewish literature is always a work in progress.

Rebecca Goldstein

Rebecca Goldstein

Rebecca Goldstein is the author of 10 books. She received the 2015 National Humanities Medal, the 1995 National Jewish Book Award and was a 1996 MacArthur Fellow.

I’ve stopped reading all novels that would fit neatly into the category of American Jewish fiction. This is partly because I’ve stopped reading almost all contemporary fiction, since, in the past decade my focus has returned almost exclusively to philosophy. But I have to confess I was turned off by the way that this category, American Jewish fiction, began to be “worked” in a manner that struck me as self-conscious and inauthentic. A novel, for me, loses its allure if it suggests, as fundamental to its sensibility, its membership in any such category. There are some genuinely interesting and ambitious novels that have Jewish authors and Jewish characters, and where such themes as Jewish history or the meaning of “Jewishness” are central. Rachel Kadish’s recently published The Weight of Ink (2017) is a good example. But precisely because these novels are genuinely interesting, they are entities unto themselves. For me, nothing is added—but rather something is subtracted—by discussing them in the context of “American Jewish literature.”

I think that this was different in the previous age of Saul Bellow and Stanley Elkin, I.B. Singer and Grace Paley. They weren’t working the category of American Jewish literature, but rather, the category burst organically forth from their work.

Afterword

American Jewish literature is alive and well. Literature inspired by the great 19th- and 20th-century Ashkenazi waves of immigration, may or may not be exhausted (I don’t think it is), but the literature of other Jewish émigrés to America is still young. We have already seen flowerings of Russian-Jewish American literature—Gary Shteyngart, Boris Fishman, Paul Goldberg, Anya Ulinich and others—and Egyptian-Jewish-American writing—Lucette Lagnado and André Aciman, for example. Literature written by Israeli-Americans now living in the United States is yet another branch beginning to emerge, with writers such as Shelly Oria exploring the chasm between American and Israeli culture. These and other American Jewish communities that we have heard less from all have their own stories to tell. It should be clear by now that American Jewish literature is as complex and as varied as the DNA of American Jews.

Ethnicity and geography account for only some of the wrinkles from which new literature is taking shape. Regardless of where a writer grows up, he or she faces contemporary dilemmas that can give birth to great writing. The upsurge in anti-Semitism in this country, for example, is bound to find expression. Internally, the American Jewish community is as conflicted as ever, which is always good for writers. We’ve heard from many writers who have fled the confines of ultra-Orthodoxy and those exploring what it means to be LGBTQ, but there are many more knots to untie. American Judaism itself is an infinite source of conflict. With so much fodder remaining for great American Jewish literature, I fully expect writers who have yet to make their names to take us by surprise. But given our predilection for the familiar and the insular nature of the book industry, it’s far too easy to be blinded by what has come before. As readers, it’s our responsibility to be on the lookout for new writers. Let’s welcome them! —Nadine Epstein, Moment editor-in-chief