© Rafael Suanes/Georgetown University

By Nadine Epstein

One of the lesser-known heroes of World War II was Jan Karski (1914-2000), an officer in the Polish Underground resistance who infiltrated the Warsaw Ghetto twice. Later, he posed as a Ukrainian guard at the Izbica transit camp where he witnessed Jews being herded onto trains to be sent to their deaths at Belzec, the extermination camp. His efforts to alert American and British leaders to the Nazis’ intention to annihilate the Jews fell on deaf ears. Although his 1944 book, Story of a Secret State, sold well, he was forgotten after World War II. Only decades later were his courageous actions recognized: In 1982 Yad Vashem awarded him the title of a Righteous Among the Nations, and in 2012, 12 years after his death, he was given a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

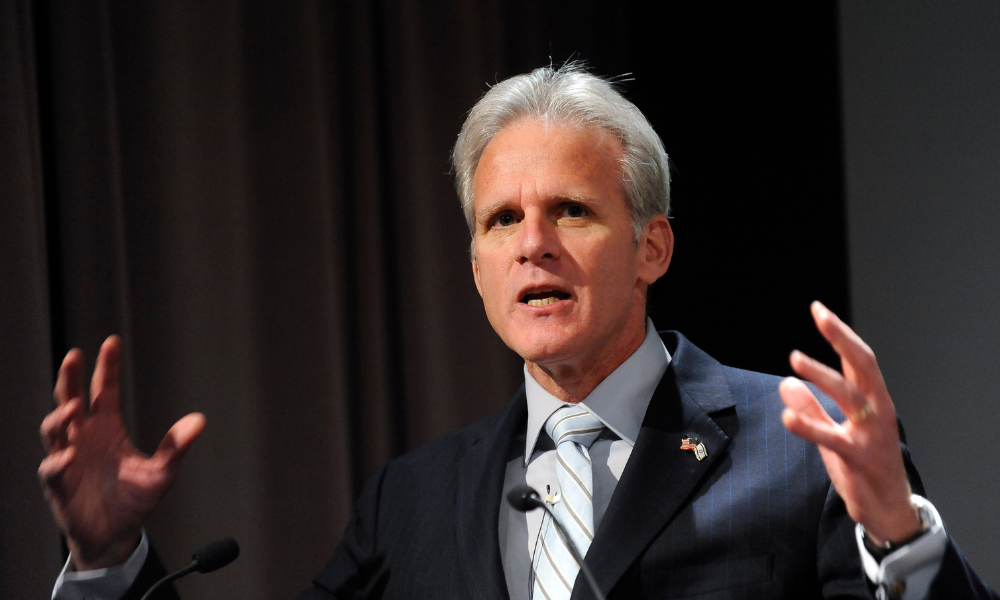

This past April, actor David Strathairn took on the role of Karski in a dramatic reading of Derek Goldman’s play, Remember This: Walking with Jan Karski, at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. Goldman, a Georgetown professor of theater and performance studies, reached out to Strathairn, a veteran of landmark films such as George Clooney’s 2005 Good Night, and Good Luck (he was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance as the iconic broadcaster Edward R. Murrow) and Steven Spielberg’s 2012 Lincoln (he played Secretary of State William Henry Seward).

Strathairn was thrilled to take on the enigmatic Karski, who in the play is interviewed by his students. In late October, the actor will reprise the role at Theatre Imka in Warsaw in conjunction with the opening of that city’s new Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Moment editor Nadine Epstein talked with him about Karski’s significance and the challenge of embodying major historical figures.

Why did you want to play Jan Karski?

Karski is an extraordinarily compelling figure in history. His life is so moving and heroic in such a quiet way. He’s part of an age-old tradition of whistleblowers, people who bear witness to events. He put himself in grave danger, and I believe saw it as his mission, his duty, what he was on Earth for. And then he came to the West and President Franklin D. Roosevelt sort of listened to him, but nothing really happened. Then he went to Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, and Frankfurter said, “I don’t believe you. I don’t mean to say that you’re lying, but I don’t believe that this could happen.”

What happened after that?

Karski taught at Georgetown University for about 40 years and never mentioned what had happened until filmmaker Claude Lanzmann found him and filmed him for Shoah. His colleagues and his students all those years at Georgetown had no idea. Just thinking of what it took for him to be silent for all those years, and why he was, boggles the mind. I can see that the response of the highest people in the land in the West made him think, “Well, I can do no more.”

What did you learn about Karski from your research that surprised you?

He said he was an insignificant little man and that it was his mission that was important. To think of him thinking of himself as an insignificant little man is an insight into who he was as a person.

What was it like to play Karski?

It was an unbelievable privilege and an honor. It was also a bit intimidating, because whenever you are asked as an actor to give some kind of presence to an historical character, there’s so much responsibility attached to it. Not only to respect that person’s legacy, but to be respectful of who they were and try not to do anything more than say their words and be inside their spirit as much as you can. You don’t want to do any kind of revisionism or paint their portrait in a way that is not truthful to them. It’s a challenging and exciting process, but you always fall short.

How did you prepare for the role?

Fortunately there are videos of him, so I could try to get a reasonable facsimile of how he spoke. He was Polish, so I tried to get his sound. You can bring to the table what he was wearing, how he looked, how he carried himself—basically the impersonation. You’re trying to give an affectation of his presence that’s as respectful and as unadorned as possible. All that goes into creating a character, but when it comes to the person’s soul, their mind, their psyche, that’s like grasping and trying to hold on to fog. It’s there and it’s seemingly palpable. You think about it, but to actually grab onto it, that’s hard.

Throughout your career, you’ve played characters like Edward R. Murrow and William Henry Seward. Do you gravitate toward historical figures?

I don’t gravitate toward them, but when they come your way it’s a real privilege. You’re lucky if you get asked to do them. Not only are they are a huge challenge to do, but you learn so much about that particular time in history and about great people.

How does one honor a man like Karski?

We need to keep his name alive by keeping his deeds alive in whatever way we can. There is a wonderful little adage that you’re never gone until the last person on Earth forgets your name. We are only as aware of ourselves as we are of our past.