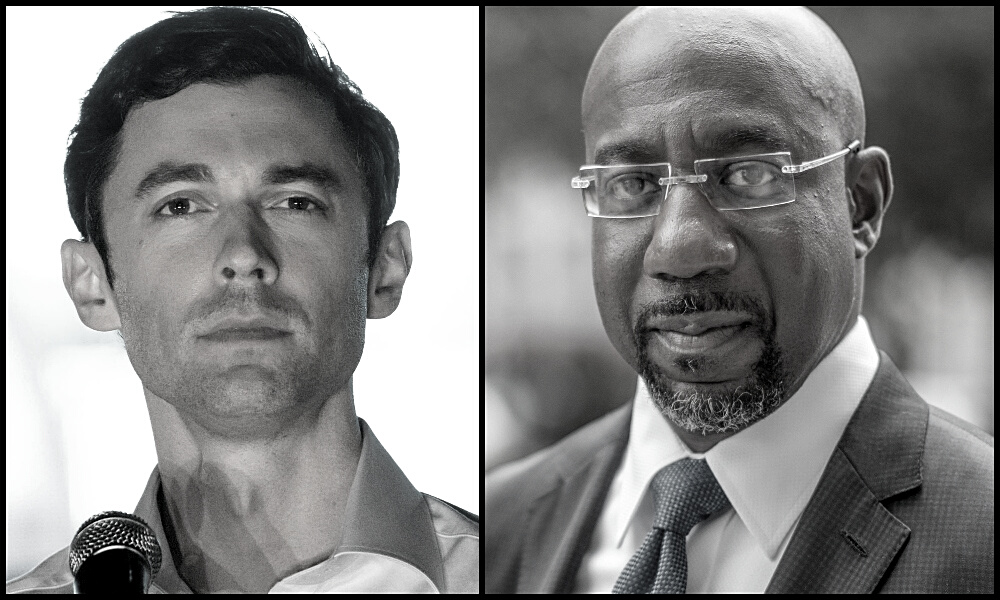

DEBATERS

Jed Rubenfeld, a constitutional scholar, has advised parties on possible litigation against Google and Facebook.

Paul M. Barrett is deputy director of the NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights and coauthor with J. Grant Sims of False Accusation: The Unfounded Claim That Social Media Companies Censor Conservatives.

INTERVIEW WITH JED RUBENFELD

Should the First Amendment Apply to Social Media? | Yes

Should the First Amendment apply to social media platforms?

Yes. We’re living with an unprecedented threat to free speech, with much of today’s public discourse controlled by a handful of companies with unsurpassed wealth and power—companies whose capitalization values exceed the economies of major developed countries. They have more power over public discourse than any entity, private or public, has ever held. No U.S. governmental entity can exercise viewpoint-based control over even the smallest corner of public discourse, yet Facebook editors do this every day on a massive scale, deciding what can be heard and seen.

What demands can the government make on social media companies?

When radio first emerged, then a revolutionary new medium of communication, two or three companies soon controlled the entire infrastructure. The same happened with TV. The federal government adopted the Fairness Doctrine, which didn’t apply the First Amendment to the networks but instead said they had a legal duty to cover public affairs fairly and present differing views.

I don’t think the Fairness Doctrine solves our present problems, because I don’t want a government agency like the FCC to decide what counts as a fair presentation of different sides of an issue. Instead, Big Tech internet platforms should be viewed as government actors, subject to the First Amendment’s requirements when they seek to restrict speech. I think that’s the only way we’re going to be able to preserve freedom of speech.

How can you restrict dangerous speech yet avoid viewpoint discrimination?

There’s a century of First Amendment law on this. The principal test is whether the speech constitutes incitement. If so, there’s no problem with platforms removing or blocking it. Doxxing could also be restricted because it reveals private information about a particular individual, and prohibiting it isn’t viewpoint discriminatory. What about dangerous speech that doesn’t cross the line into incitement? If there’s a real threat of imminent harm, it can probably be temporarily blocked, but you can’t punish the person by permanently de-platforming them. A governmental actor who sought to de-platform a person, as was done to President Donald Trump, would immediately be recognized as violating the First Amendment.

Big Tech internet platforms should be viewed as government actors, subject to the First Amendment.

If the government ran Twitter, would we allow it to stamp somebody’s page FALSE or MISLEADING? We’d find that constitutionally highly problematic. Speech that’s been proven false can be removed or blocked as libelous. But for most statements, we don’t want the government deciding what’s false. It’s very difficult to prove a negative—say, that someone did not win an election.

Are Facebook and Twitter more like private rooms? Shopping malls? The public square?

I don’t think any of these analogies will help. Social media is something else entirely. One big difference is that Congress has encouraged and induced Big Tech to censor speech. Section 230 expressly says they’re immune from liability if they block “objectionable” but “constitutionally protected” speech. In other words, through Section 230, Congress is using Big Tech as its agent to censor speech online, which Congress couldn’t do itself. At the same time, Congress is putting pressure on Big Tech platforms to curb dangerous and extremist speech. Every year there are more hearings asking why they haven’t taken more steps. They’re immunized, then pressured by the government to do it: That clearly tips the scale and turns them into state actors.

The Supreme Court recognizes that the government can’t induce private parties to commit unconstitutional acts. What if a state immunized people from liability for blocking access to abortion clinics and then pressured them if they didn’t? Anyone who thinks that would be a constitutional result is not seeing the big picture.

Do we have too much speech or not enough?

No one really knows whether having an American-style First Amendment leads to a better society. Some Asian countries do well at suppressing pandemics and poverty—so people get drawn to the idea that more autocracy and less freedom will lead to better results. The First Amendment is a bet that that’s not so—that if you suppress people from speaking freely, in the end you’ll provoke more violence, more bloodshed and worse policies because they won’t be vetted by criticism. Some people say the internet has changed that bet so it doesn’t work anymore. But that’s what they said about radio, about television. The internet’s history is just starting; it’s way too early to give up on the First Amendment.

A lot of constitutional scholars say there’s a free market in ideas and that true ones will win the day. It would be nice to believe this, but I don’t know if it’s true. Falsehoods often win the day, no matter how much speech you have. People love to believe false things if it suits their interests. We protect speech not to guarantee truth but to guarantee freedom.

Do Jews have a special interest in the First Amendment?

Absolutely. Any religious minority does. And Judaism’s long tradition of debate and argument and questioning widely held beliefs also depends on freedom of speech.

INTERVIEW WITH PAUL M. BARRETT

Should the First Amendment Apply to Social Media? | No

Should the First Amendment apply to social media platforms?

No. It doesn’t, and it’s proper that it doesn’t, even though those platforms do present very complicated problems related to speech. These platforms have failed to adequately police themselves in spreading harmful content. As a result, people engaged in this area are thinking actively, though with some reluctance, about a way for government to provide the regulation that the industry is not providing itself.

In doing that, the government has to be very vigilant about not making decisions that relate to content. The First Amendment is primarily directed toward preventing the combination of the core power of the government with the power to censor. The government can arrest you and regulate your behavior. You don’t want to combine that power with the power to say who can speak.

What demands can the government make on social media companies?

Government can require that companies give their users more information about how they rank and recommend content. If companies have to explain more about how their algorithms actually work, they have an incentive to make them better. Once their practices are exposed to public scrutiny, unhappy users could force companies to improve or be more transparent.

It makes sense to keep to the principle that the First Amendment forbids censorship only by the government.

The existing law, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, actually protects those companies from being sued for decisions they make in the course of content moderation, and it’s designed to encourage them to do more of it. I think the law should be updated to reflect the bad side effects social media has had. Probably the simplest way is to create more exceptions to the companies’ immunity from being sued, in areas such as hate speech, harassment or civil rights abuses, so they’ll become more vigilant in these areas. There’s legislation currently being sponsored to that effect.

How can you restrict dangerous speech yet avoid viewpoint discrimination?

There’s a danger, and we have to be careful. But there is no evidence that companies disfavor conservative content. I was the co-author of a recent report looking into the claim that social media censors conservatives, and we concluded it’s completely unfounded. There are many anecdotal examples of prominent right-wing figures having content taken down, but when you examine those examples, you find it’s because they violate the rules of the platform. That’s true from Alex Jones of Infowars to former President Donald Trump.

As for Trump, I think it was legitimate for Twitter to ban someone who had repeatedly violated its rules against inciting violence and, in the aftermath of the Capitol riot, had ignored warnings to stop using Twitter for what his followers themselves identified as incitement. It’s fine for Twitter to say, “We’ve had enough of this guy.” Not because he was conservative but because he said, essentially, “Let’s get together in this place on this date and do things that are illegal.”

The Supreme Court struggled with the question of dangerous speech in the 1960s and 1970s, in a completely different speech environment, and came up with a formula about imminence of actual violence and the intention of the speaker to provoke that violence. Facebook and Twitter can come up with their own rules, and it’s important that those rules be clearly stated and fairly enforced. But there’s no reason the sponsor of a platform can’t say, “You can’t use our platform to incite violence.” That’s not controversial at all.

Are Facebook and Twitter more like private rooms? Shopping malls? The public square?

In 2017, Justice Anthony Kennedy referred to social media platforms as the modern public square. In my humble opinion, that’s not completely correct. No one social media platform is the only venue on which to express yourself. Trump is going to have no difficulty finding outlets for his views in coming months.

If you decided that Facebook was the public square and First Amendment protections applied to it, it would look very different very quickly, overrun by porn and constitutionally permitted hate speech. It makes sense to keep to the principle that the First Amendment forbids censorship only by the government.

Do we have too much speech or not enough?

There’s a traditional First Amendment attitude that you can never have too much speech. On the other hand, we are seeing the social unrest that comes with the spread of disinformation through social media, especially in other countries where democratic institutions are less deeply rooted. From Myanmar to Brazil, digital tools have been used to spread falsehoods that lead people to be killed on a genocidal scale, or to authoritarian political leaders gaining power, and it’s all very troubling.

Do Jews have a special interest in the First Amendment?

Yes, of course. As a minority religion, we value dissent. And we’re concerned about the misuse of prominent platforms, because all too often Jews are singled out as the target of hate speech, conspiracy theories and disinformation.

I agree with Jeb Rubenfeld. A free society must have free speech. Censoring chokes off the ability for all people to exchange ideas; to debate; to share experiences and it leads to a “ Forced March” of conformity and mediocrity.