The last time I walked through the medina in Marrakesh, Morocco, it was 1972 and I, a hippie between college and graduate school, was living in accommodations I could afford: the Marrakesh campground. Each day I’d head to the medina, the old city, and lose myself in the maze of narrow pathways, a labyrinth laden with history, echoing the sounds of centuries.

Little did I know that those echoes were the chants of my ancestors. I had been wandering the warrens of the mellah, the Jewish quarter, where for generations, Jewish merchants sold their wares, women prepared for Shabbat and wooden doors opened into intricately tiled sla’ats or synagogues, welcoming Jewish families and grand rabbis.

Signs of that Jewish community, once the largest in the Arab world, are everywhere—if you know where to look: A Star of David inlaid in the wood paneled lobby of my elegant riad in Essaouira. The whitewashed Jewish cemetery, reflecting the morning sun in Fes. The intricate silver and brass work, originally tooled by Jewish craftsmen in the souks of Marrakesh. These are our ancestors’ testament, as if they are saying, “We were here, this was our home.”

A Star of David inlaid in the lobby of the luxuriously restored riad Heure Bleue in Essaouira. (Gail Dubov)

Morocco has been home to Jews since their exile from Jerusalem after the destruction of the First Temple in the 6th century B.C.E. Later, Jewish traders arrived with the Phoenicians, founding communities that grew into Casablanca, Rabat and Essaouira. Others lived peacefully for the next 2,000 years with Berber tribes in the Atlas Mountains, speaking the Berber dialect, and intermarrying.

In 15th-century Fes, the Sultan moved the city’s Jews to a walled area in the shadow of the palace, the mellah, meaning “salt,” and named, according to some historians, for its location near salt deposits. The purpose: to protect, not punish, his Jewish subjects. Known as dhimmi, or “protected persons,” they were free to practice their religion, but (and for Jews through history, there always seems to be a ‘but’) they were barred from certain occupations and charged a poll tax.

Fleeing the Inquisition, Jews from Spain and Portugal flooded Morocco after 1492, following in the footsteps of the brilliant Andalusian scholar Maimonides, who had arrived 300 years earlier. Small Sephardic communities thrived as the new immigrants shaped their careers as bankers, tailors, jewelers and craftsmen.

Before the founding of the State of Israel, there were more than 250,000 Jews in Morocco, scattered throughout the country in almost 100 communities. Today, barely 3000 Jews remain. The migration started after World War II when ships began arriving from Israel to populate the new nation. Within three years, almost 30,000 Moroccan Jews packed their suitcases and left.

Fear that Morocco’s independence from France would lead to Jewish persecution caused the next wave of emigration. “Our Muslim neighbors begged us to stay,” explained a Moroccan Israeli who was back in her homeland for the first time since 1955. “But my father was afraid, so we left,” she continued with a hint of melancholy.

Scattered throughout the world, most Moroccan Jews settled in New York, Montreal, Paris and Tel Aviv. Now, the dusty synagogues and crumbling Jewish quarters they left behind are being given a second life.

Marrakesh

Jacky Kadoch, president of the Jewish community of Marrakesh and Essaouira. (Gail Dubov)

When the leader of Marrakesh’s Jewish community, the affable Jacky Kadoch, requested the city’s Jewish quarter return to its original heritage, King Mohammed VI issued an order to oblige “to preserve its historic memory.” Thirty years before, hundreds of original Jewish street signs were removed, replaced with Arabic names.

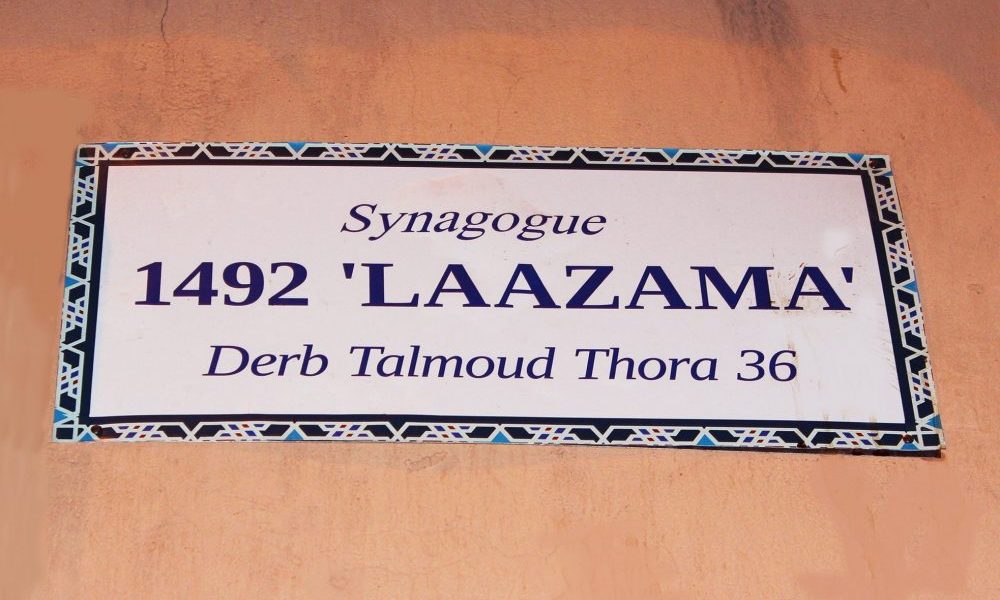

Walking through the mellah of Marrakesh, our guide, Hamid, points out the name of the street on which the still-active Lazama synagogue had been built in 1492: Talmud Torah Street. The signage, clearly new, hangs on ancient ochre walls. This is part of a $20 million project by the king to restore the old quarter of Marrakesh and preserve Jewish heritage throughout the country. The kingdom has restored mellahs, dozens of Jewish schools, cemeteries and more than 100 synagogues.

A return of Jewish street signs in the Marrakesh mellah, as ordered by the King. (Gail Dubov)

“There once were 30,000 Jews living in the quarter,” explains Kadoch at breakfast one sunny morning in Marrakesh. Wearing a dapper straw fedora covering his kippah, he continues, “In the 50s and 60s Jews started moving to Israel, and by the 80s the numbers were very low.” Today 300 remain, many old and poor, living under Kadoch’s caring eye.

“I was born in the mellah and went to the yeshiva in the quarter,” Kadoch, also leader of Marrakesh’s Beth El Synagogue, adds. But his family, like many others, soon moved to a new, more affluent area. Today, he and his wife travel to Montreal to visit his children and grandchildren. One son has just returned, but with slim prospects of finding a Jewish wife, he will probably not remain. And so goes the fate of the next generation.

Casablanca

With 2,000 Jewish residents, 30 synagogues, kosher restaurants, a Jewish cemetery and many Jewish schools, Casablanca is home to the largest Jewish community in the Arab world. It also houses the only Jewish museum. Tucked away on a quiet residential street, The Museum of Moroccan Judaism is the keeper of Jewish history. Once an orphanage for Jewish children, the museum showcases centuries of Jewish ephemera in a space renovated with government and private funds.

Temple Beth El, the centerpiece of Casablanca’s Jewish community. (Gail Dubov)

Its director, Zhor Rehihil, a Muslim woman with a Ph.D. in Jewish studies, points out highlights of the collection: Torah scrolls, chamsas, hanukiah, elaborately embroidered caftans, a carved wooden bimah. “As Muslim Moroccans, we feel we lost a part of our identity when Moroccan Jews left the country,” explains Rehihil. “We used to have a six-pointed star on our flag, like Israel. But under French rule it was changed to five.”

Temple Beth-El (or Beit El), established by Algerian Jewish immigrants, is the centerpiece of Casablanca’s once vibrant Orthodox community. Modern stained glass windows add splashes of color to the classical interior with its elegant chandeliers.

The windows of Casablanca’s Temple Beth El are reminiscent of those of Marc Chagall. (Gail Dubov)

Fes

The mellah in Fes, the oldest in the Kingdom, is strikingly different from the rest of the city. The Jews favored balconies, reminiscent of their homes in Andalucia, that overlook the street rather than the inward facing courtyards with plain facades of their more modest Muslim cousins. Its medina, the largest in the world, houses the Slat al Fassayine Synagogue, the oldest in the city, which was renovated in 2013 by a Moroccan and German government partnership.

Balconied houses were signs of Jewish homes in the mellah. (Gail Dubov)

Simple wood doors hide the 17th-century Ibn Danan Synagogue, built by a wealthy merchant. Our Muslim guide, Fatimah Zahra, is the third-generation caretaker of this synagogue. She points out the wooden bimah with a wrought iron canopy of Islamic style arches, and a hole in the geometric tiled floor, a peephole into the ancient mikvah below.

The renovated cemetery of Fes contains more famous rabbis and saints than any other in the country. (Gail Dubov)

The restored Jewish cemetery, Beit HaChaim, at the edge of the mellah, is home to more saints and famous rabbis than any other cemetery in the country. Neat rows of white arched tombstones, some with small chambers for burning candles, slope gently down a hill. Larger tombs announce the burial spot for rabbis. One sepulcher houses the Jewish saint, Solica Hatchouel, a young woman killed in 1834 for her refusal to convert to Islam.

An original street sigh in the old mellah of Fez. (Gail Dubov)

Essaouira

As we walk past the bright blue fishing boats on a windy day in Essaouira, our guide, Rashid, fills us in on the city’s pop history. “Jimi Hendrix lived here,” she explains. “Part of Orson Welles’ Othello was filmed here. So was season three of Game of Thrones,” she tells us, proudly.

A remnant of the Jewish community in the coastal city of Essaouira. (Gail Dubov)

But more importantly, she points to a stone arch where, if you look carefully, a weatherworn Star of David is carved. In 1764, she explains, the sultan recruited ten prominent Jewish merchant families to transform the city—then called Mogador—into a major port of international commerce.

Tomb of Haim Pinto in the old cemetery, site of an annual pilgrimage, Essaouira. (Gail Dubov)

At one time Jews made up half the population and there were more than 40 synagogues within the city walls. Some, like the Simon Attia, currently being restored, were the private synagogues of large families. Others, such as the Slat Lkahal, were community centers of worship. The holiest site is the grave of Rabbi Haim Pinto, the most respected religious leader of Moroccan Jews, known for performing miracles. His mausoleum, in the middle of the old cemetery, draws thousands of visitors each September for an annual hiloula (pilgrimage). The renovated Haim Pinto synagogue and the Slat Lkahal are in the historical mellah, part of a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Haim Pinto synagogue in Essaouira. (Gail Dubov)

The cities of Rabat and Meknes have their own mellahs and other signs of a once-active Jewish community. Traces of one can also be found in Volubilis, an excavated, ancient Roman city near Meknes.

The King Who Saved His Jews

In 1940, the French Vichy government demanded the names of Morocco’s Jews from King Mohammed V. The monarch refused to cooperate with the Nazi regime. Defiantly, he responded, “There are no Jews. There are no Muslims. There are only Moroccan subjects.” Though France controlled Morocco throughout the war, no Moroccan Jews were ever sent to concentration camps or forced to wear a yellow star.

This heroic act—unknown by most—underscores Morocco’s longstanding protective, tolerant spirit towards its Jewish subjects. In 2011, further reinforcing it, the Moroccan constitution was changed to note that the country has been “nourished and enriched…[by] Hebraic influences.”

I felt that spirit in every renovated synagogue, every restored mellah, in the echoes of a Friday night service, in the dinner at a kosher cafe. A new life is rising up from a vanishing population.

This is a wonderful view of Moroccan Jewish life and history. An inspiration for this reader to make a journey to Morocco, which I have previously visited, but this time with eyes wide open to our history. Thank you, Ms. Dubov, for your keen eye for historical detail.

Wonderful overview and history of Jews in Morocco–then and now. Sure wish I knew that when I vagabonded around this breathtaking country back just about the time this fabulous journalist must have been calling the Marrakesh campground “home!” What a great piece! Thank you!

On ne peut Que remercier Sa Majesté Hassan VI qui continue comme son père et son grand père ,qu’ ILS REPOSENT en paix , cette tradition du respect des autres et fait beaucouppour la communaute juive marocaine.

Nous anciens marocains lui souhaitons une bonne sante et meme en Israel nous prions pour lui. Que D’ lui accorde longue vie et tout le bien possible pour continuer à diriger le royaume

how interesting that the present King is able to carry on with the works started by his father and grandfather and other Arab leaders do not attempt to stop him or attack him. A wonderful example of how life could and should be between Jews and their Arab neighbours, if only it could be like this in the rest of the Middle East. A really good reason to visit!

Fascinating article, but Maimonides died in 1208.

“After 1492, fleeing the Inquisition, Jews flooded Morocco from Spain and Portugal, including the brilliant Andalusian scholar Maimonides. ”

Maimonides died in 1208 . He lived in Morocco during the 12th century.

Thanks Josef. Editing error which I’ve corrected. Appreciate!

“With 2,000 Jewish residents, 30 synagogues, kosher restaurants, a Jewish cemetery and many Jewish schools, Casablanca is home to the largest Jewish community in the Arab world.”

Iran has a bigger community than Morocco with almost 10,000 remaining.

Wonderful article, an inspiring historical introduction to my upcoming trip to Morocco! Thank you!

I positively thought it valued it – and this tour was truly great!

Thank you for your exclusive sharing…enjoy the genuine Trip