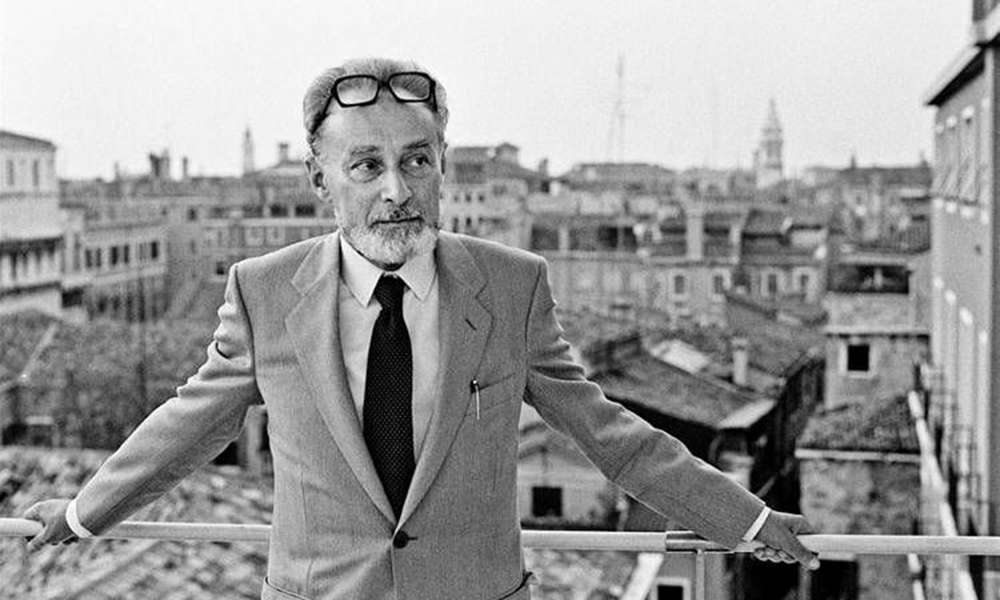

As the July 31 centenary of Primo Levi’s birth approached this past summer, Italy paid homage. For the chemist turned writer who, along with Elie Wiesel, cofounder of this magazine, remains widely acknowledged as one of the foremost literary witnesses to Auschwitz’s horror, the outpouring of appreciation marked unmistakable confirmation that Levi would not, like so many important writers after their death, slip from public importance.

Two of the nation’s leading newspapers—Rome’s La Repubblica and Turin’s La Stampa—bundled books by or about Levi with their Sunday editions. On the centenary itself, all three of Italy’s top newspapers published multiple essays about him, with La Stampa scooping everyone by running a lovely, previously unpublished piece by Levi entitled, “I Write Because I Am a Chemist.” RAI Cultura, the country’s national broadcaster, aired a documentary about Levi the same day.

In the United States, the New York Public Library organized an eight-hour reading in multiple languages of If This Is a Man, also translated into English as Survival in Auschwitz. In Lisbon, preparations began for the exposition “The Worlds of Primo Levi: A Strenuous Clarity,” organized and curated by the Centro internazionale di studi Primo Levi in Turin, a show that will later come to the United States.

If one could discern a unifying theme in many of the remembrances, it might be Paolo de Stefano’s recognition, in “The Sentinel Primo Levi,” of “the three-dimensionality of a writer who for years has been loved especially as a witness.” One Italian critic after another commented on the often-ignored diversity of Levi’s work, supporting the writer’s own plea at one time that he did not want to be viewed as merely a “Holocaust writer,” but solely as a scrittore, a writer, with no adjective limiting that sanctified status.

Perhaps the most notable aspect of the tributes was their redirection of attention from the last enormous wave of journalism about Levi—after his death at 67 on April 11, 1987. On that morning, only minutes after answering the doorbell of his third-floor apartment and thanking the concierge for his mail, Levi plunged down the stairwell of the Turin apartment building, Corso Re Umberto 75, where he’d lived all his life.

His death stunned the literary world. Had Levi committed suicide in a manner that utterly contradicted everything intimates said later they had thought they knew about him—his scientific precision, his dexterity with chemicals, his kindness, his will to survive, his opposition to suicide? Would such a man not leave a note? Or had he suffered some neurological event that caused him to fall?

In the years since his death, scholars, biographers and those who knew him remain split on the issue. Several biographers came to believe it was a suicide, while many who knew him (including this critic) continue to reject that conclusion. In fairness, attention to the issue can’t be ridiculed as mere literary sensationalism, even if neither side saw the centenary as an appropriate time to raise it again. Given the nature of Levi’s principles, separating the suicide question from his work requires finesse. If even Levi, the voice of cool, rational coping with the trauma of Auschwitz, could take his own life, maybe the possibility of psychologically surviving the Holocaust didn’t really exist.

As his literary reputation rose around the world, Levi stood as the stoic Holocaust survivor who analyzed his experience in Auschwitz as a scientist—dispassionately, precisely, without letting sentimentality get in the way of the facts. Speaking with Philip Roth, he likened If This Is a Man to a factory “weekly report,” the clear, accessible genre he practiced after the war as a chemical engineer managing a paint factory. But his later works expanded far beyond that genre. The Periodic Table, in which every chemical element triggered a story from his past, made him famous. The Monkey’s Wrench, an exuberant novel about a rambunctious construction worker, confirmed his creative touch; and The Tranquil Star, a collection of his inventive short tales and “science fables,” revealed him as far more than the documentarian of Auschwitz.

Over the years, many other writers and intellectuals who survived Auschwitz—the Austrian philosopher Jean Améry, the German-language poet Paul Celan, the Polish writer Tadeusz Borowski and others—committed suicide. But Levi always rejected that “solution.”

In 1979, he wrote of Auschwitz, “My time there did not destroy me physically or morally, as was the case with other people. I did not lose my family, my country, or my home.” Later, in The Drowned and the Saved, his last collection of essays on Holocaust themes, Levi drove home the point: “Auschwitz left its mark on me, but it did not remove my desire to live. On the contrary, that experience increased my desire, it gave my life a purpose, to bear witness, so that such a thing should never occur again.”

Those of his admirers who believe he committed suicide concluded that Levi’s resolve had finally failed him. Wiesel famously remarked, “Primo Levi died at Auschwitz 40 years later.” Leon Wieseltier, then literary editor of The New Republic, wrote, “He spoke for the bet that there is no blow from which the soul may not recover. When he smashed his body, he smashed his bet.” Italian novelist Natalia Ginzburg observed that despite Levi’s claims in his writings, he “must have had terrible memories” that “led him toward his death.”

Eventually, more casual observers came to treat the matter as a proven fact rather than one possibility. As recently as 2015, the chronology at the beginning of editor Ann Goldstein’s three-volume edition of The Complete Works of Primo Levi, published by Liveright, stated flatly, “April 11: Levi dies, a suicide, in his apartment building in Turin.”

The strongest argument from the other side came in a 1999 Boston Review article titled “Primo Levi’s Last Moments,” by Oxford sociologist Diego Gambetta. Gambetta weighed a range of possibilities: premeditated suicide because of Holocaust demons; premeditated suicide for other reasons; spur-of-the moment suicide for any combination of reasons; a fainting spell; a bad reaction to medicine.

Gambetta argued that if Levi had planned his suicide, he “would have known better ways than jumping into a narrow stairwell with the risk of remaining paralyzed.” He rejected the idea that Levi—sober, restrained, fastidious and intensely concerned with the dignity of himself and others—would have imposed such a horrific scene on his family and neighbors.

Gambetta conceded that Levi, at the end of his life, suffered from chemical depression unconnected to the Holocaust and took antidepressants; that he’d undergone a prostate operation just 20 days before his death; that both his senile, nonagenarian mother and his mother-in-law were slowly dying. Nonetheless, Gambetta favored the judgment of a cardiologist friend of Levi’s that his antidepressants might have triggered a dizzy spell that caused him to fall over the stairwell’s low banister.

Some Levi scholars found Gambetta’s arguments convincing. “I never thought it was suicide,” commented Risa Sodi, author of A Dante of Our Time: Primo Levi and Auschwitz. Another, Lina Insana, who teaches Italian studies and Holocaust literature at the University of Pittsburgh, said, “I never believed it was a premeditated suicide.” The Nobel Laureate Rita Levi Montalcini, a lifelong friend of Levi’s, also reportedly rejected the idea of suicide.

I first met Levi after reviewing The Periodic Table (1984); I visited him at his apartment and well remember that low stairwell banister. I agreed with the skeptics. The idea of Levi—exact, analytic, usually undemonstrative except for his wry smile and controlled laugh—suddenly hurling his body into space seems as likely as Marcel Proust secretly lifting weights, or Umberto Eco faking his familiarity with Latin.

Now, more than 30 years later, the silence of the Primo Levi centenary commentators about this once volatile issue recalls a lesson worth remembering—a lesson Levi delivered in The Drowned and the Saved. There he wrote that suicide “allows for a nebula of explanations.” He deemed it “an act of man and not of the animal. It is a deliberate act, a non-instinctive, unnatural choice.” He also reminded us that it is human nature to want to simplify, even when simplification is not “justified.”

In the most famous anecdote in all his writing, Levi recounts in If This Is a Man how, parched with thirst, he tried to grab an icicle through his cell window only to have a Nazi guard snatch it away. When Levi asked “Warum?” (“Why?”), the guard replied, “Hier ist kein warum” (“Here there is no why”).

Regarding Levi’s death, here there is no how, no what, no answer—beyond his inimitable, immortal, incisive body of work.

Carlin Romano, Moment critic-at-large, teaches media theory and philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania and is the author of America the Philosophical.