The Weird and Wondrous World of Jews and Magic

The first time I came face-to-face with Jewish magic was when I moved to Israel in my early 20s. It was the fall of 1995...

Anti-Semitism Watch | Germany’s Far-Right Is Changing the Political Landscape

In August, far-right mobs in the eastern German town of Chemnitz hunted foreigners through the streets. In the chaos, a kosher restaurant was attacked and...

Becoming a (Jewish) Grandparent

Four months ago, our daughter gave birth to our first grandchild.

Democrats Bet on Jacky Rosen

No pressure, but the fate of Democratic dreams to win control of the U.S. Senate in November may hinge on one Nevada freshman congresswoman, whose previous experience in public life was as president of her synagogue.

Meet Our Caption Contest Contributors: Stephen Nadler

Nadler was a finalist for the first four Moment cartoon caption contests he entered.

Meet Our Caption Contest Contributors: Dinah Rokach

It’s never too late for some good, old-fashioned sibling rivalry—not even in retirement.

Meet Our Caption Contest Contributors: Dale Stout

"I’ve probably won 80-plus contests and been a runner up for more. It’s just persistence."

Meet Our Caption Contest Contributors: Adrian Storisteanu

"I have to confess I don't actually put actual work or much thinking in this enterprise, but instead rely on sudden spurts of inspiration."

Meet Our Caption Contest Contributors!

We wanted to learn more about our most prolific participants—so we asked them about their love of contests, their approach to humor and the secret to the perfect caption.

Can Hebrew Be Gender-Neutral?

Gender in Hebrew—as in Spanish, Hindi, French and other languages—is intimately woven into word construction. “Hebrew goes a lot further,” says Erez Levon, a professor of sociolinguistics at Queen Mary University of London who focuses on questions of gender and sexuality. He explains that the language is particularly restrictive because gender is conveyed through masculine or feminine verb, adjective and adverb endings and almost every other part of speech.

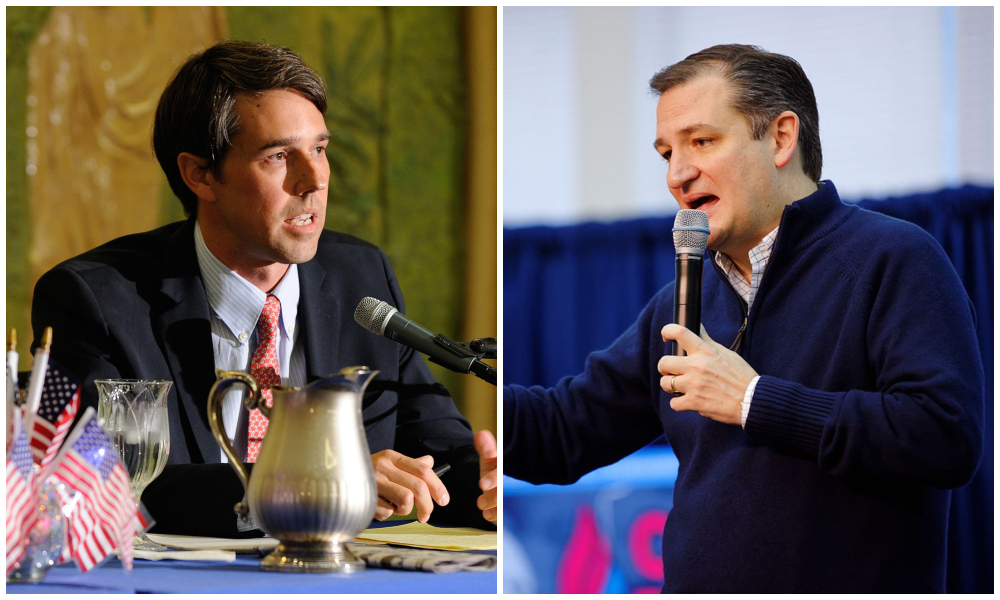

Beto O’Rourke Runs the Israel Gauntlet

Jews make up less than one percent of the Texas population. And yet the “Israel question” has reared its head in this year’s most-watched Senate...

Book Review | The First Book of Jewish Jokes edited by Elliott Oring

The First Book of Jewish Jokes

Edited by Elliott Oring

Translated by Michaela Lang

Indiana University Press

2018, 176 pp, $65

It’s the inherent vice of joke books that their...